|

Margate Crime and Margate Punishment

Anthony Lee

9. The Legal process at Margate.

Until the nineteenth century it was the victim who had to initiate any criminal prosecution. In the eighteenth century ‘not only assaults but virtually all thefts and even some murders were left to the general public. That meant that responsibility for the initial expense and entire conduct of the prosecution was thrown on the victim and his or her family . . . As late as the mid 19th century no public official was responsible for ensuring that even the most serious offences were prosecuted’.1 A victim would first have to identify the supposed guilty party; this was easy if the suspect was caught red-handed, but, if not, there was no modern police force to provide help. Having identified a suspect, the victim would present his case to a Justice of the Peace (a magistrate) who would decide if there was actually a ‘case to answer’. If there was and if the case was sufficiently serious, the magistrate would issue a warrant for the arrest of the suspect. For a crime committed at Margate the suspect would be held in Dover gaol, as Margate came within the jurisdiction of the Dover courts (see 1, The Justice System at Margate). It was at this point that things would start to get expensive for the victim; as well as the cost of drawing up an indictment and hiring any necessary legal help, he faced the inconvenience and cost of travelling to Dover with his witnesses for a trial.

At the trial the emphasis was on a personal confrontation between the victim-prosecutor and the defendant. It would have been highly likely that the victim, the suspect and their respective families and friends would have been well known to each other, and their relative social standing would likely influence the outcome of the trial: ‘In making their calculations, judges and jurors were influenced not simply by the abstract character of the various offences. . . . Who the prisoner was - his character and reputation - was as crucial a question as what he had done (and even in some cases whether he had done it), and it was centrally the business of the trial to find the answer’.2 All in all it is not surprising that many victims of crime chose to avoid taking the legal path at all as, of course, is still the case today. The Times in 1785 suggested that ‘nine-tenths of the breaches against the laws escape detection from the trouble and charges consequent on prosecution’.3 It was not until the mid-eighteenth century that legislation was introduced authorizing the courts to pay the expenses of the poorest prosecutors, legislation that was extended significantly in the 1820s.4,5

What all this meant was that simple disagreements between the poor would probably have been settled in private. Even those with money, and more of a social position to maintain, would avoid legal action if they could. One way was to demand that the culprit publish an apology for his actions in one of the local newspapers. As an example, in 1763, Richard Church placed an advertisement of this kind in three successive issues of the Kentish Post, apologizing to John Brasier:6

Whereas I Richard Church, of the Parish of Minster . . . Yeoman, paying too much regard to idle and malicious reports, have spoken certain words hurtful to the credit of Mr John Brasier, of Margate, Hoyman, saying he was arrested for debt, which I since find to be false – I therefore think myself oblig’d to make this public acknowledgement of the fault, and to thank Mr Brasier, for his requiring no other satisfaction for the same.

Signed in the presence of us, William Brett, Francis Cobb, John Wotton.

Sladden Wells made a similar apology in 1765:7

Whereas I, Sladden Wells, of Margate. Have lately unadvisedly said many things (which I now declare to be false) reflecting on the character of Basil Brown, Esq, of Updown, near Margate: I do hereby in this public manner ask his pardon for the same, and promise never to give him any offence for the future. And I do also return him thanks for stopping the proceedings at law, which he had commenced against me, and which might have ended to the hurt of my family. As witness my hand this 5th day of October, 1765, Sladden Wells.

As did Richard Rudd in 1791:8

Whereas I have been guilty of uttering many scandalous Aspersions on the character of Mr William Gardner, and Mr Joseph Clarke, both of this place, which I am now satisfied are false, and void of all Foundation, and for which an Action has most justly been commenced against me. Now I do hereby humbly crave their Forgivness, and sincerely hope that they will drop the Prosecution.

Richard Rudd.

This way of settling disputes continued into the early 1800s. In 1808, William Eddowes issued an apology in the Kentish Gazette:9

I hereby declare that on Wednesday night of the 14th September instant, I was at the Margate theatre, and there gave several blows to Mr Wm. Taswell of Canterbury, without having received from him, or any of his party, the smallest provocation; and that I struck the blows under the impression of having first received one, without any previous intention of insulting Mr Taswell or any of his party.

More serious cases could also be settled in the same way. In an advertisement of 1769, John Singleton, a fisherman of Margate, admitted that ‘I did most grossly assault Mr Bishop and Mr Samuel William Bishop, on Margate Pier, on Monday night . . . by which I rendered myself liable to prosecution’.10 However, the two Bishops agreed not to prosecute Singleton because of the effect such a prosecution would have on his family, as long as he made a public apology which, Singleton said in the advertisement ‘I most sincerely do.’ Similarly, Samuel Davis apologized for a violent assault on the Rev William Chapman at the race ground near Dandelion, ‘without any just cause’ and thanked him ‘for his lenity in stopping the prosecution’ he intended to start.11

Robert Salter used an advertisement to apologize for an assault on a custom’s officer in 1786:12

Whereas I, Robert Salter, of Margate . . . did on the 24th day of July 1785, assault and strike Mr Francis Hill, of his Majesty’s Cutter, the Nimble, for having on the 12th of same month fired several times for me and others (then in a boat near some East India Ships) to bring to, in order to his examining whether we had any smuggled goods on board, which it was Mr Hill’s duty to do; And whereas the Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty caused a prosecution to be commenced against me, for my unwarrantable conduct above mentioned, but from motives of humanity their Lordships have since been pleased to content to my being released and discharged from the said prosecution, upon my paying all costs, charges, and expenses; and acknowledging in this public manner their Lordship’s lenity to me; which I now do with most sincere gratitude and respect to their Lordships.

Margate, May 13, 1786.

In 1774 an advertisement was placed by George Gresham for an assault on his employer J. Croft, stable keeper at Smith’s Tavern, later known as the Royal Hotel, in Cecil Square, which arose out of underhand dealing between the stable keepers of Margate:13

Whereas on Friday the 18th of August, I did assault and ill use my late Master, J. Croft, Livery Stable Keeper, &c at Smith’s Tavern, in the presence of several gentlemen, giving him bad language, and speaking several scandalous words, which my master did not deserve. I do hereby promise, I will never be guilty of such base usage any more, and humbly beg his pardon for the said offence.

Witness my hand

George Gresham

N.B. Mr Croft’s respects to the gentlemen who have made use of his new stables, and begs the favour of them that they will not pay any more money to the said Geo. Gresham, on account of Croft’s Stables, as he now is ostler to the stables belonging to Mr Goodbarn, which the servants belonging to the Hotel inform all the Company that comes to their House, that the said Goodbarn’s Stables are the Hotel Livery Stables.

Newspaper advertisements were also used to issue public warnings, designed to prevent potential criminal behaviour. These usually referred to taking goods from stranded ships, something known locally as ‘paultring.’ In 1723 the Rev John Lewis was happy to praise the mariners of Thanet as ‘very dextrous and bold in going off to ships in distress’, but complained ‘it's a thousand pities that they are so apt to pilfer stranded ships, and abuse those who have already suffered so much . . . since nothing sure can be more vile and base, than under pretence of assisting the distressed masters, and saving theirs and the merchants' goods, to convert them to their own use by making what they call guile shares’.85 The Margate Guide of 1770 referred to ‘the acquisitions arising to the common people, from what they consider as the greatest blessing of providence - a shipwreck’.86 The guide went on to say:

They call it a God-send, and, as such, make the most of it, and are thankful . . . Misfortunes of this kind happen so frequently, that they become a good revenue to the fishermen and peasants who live along the coast, and who seldom fail to improve them to the utmost advantage. This, however, must be owned in justice to them, that, whenever there is a bare possibility of preserving a ship-wrecked crew, they act in contempt of danger, and do readily often save the lives of others, at the most imminent hazard of their own.

The speed with which news about goods washed up on shore would travel was described by the officer commanding the Kingsgate Blockade Men in 1829 87 Following the wreck of a Prussian brig, he reported: ‘Throughout the night (from 10 pm) goods were drifting on shore, in the preservation of which, and prevention of plunder, my whole party was arduously employed.’ He went on, ‘the fact of many of the inhabitants of Margate being on Kingsgate beach, during Monday night, affords . . . an evidence that the calamitous intelligence of a vessel being wrecked on the coast had reached that place; and all who came to the spot from humane motives, will, I doubt not, bear testimony to the unremitting exertion of the Coast Blockade parties to preserve property.’

It was not surprising then that ship owners and their agents felt the necessity to issue warnings about the illegality of plundering wrecked ships, such as that contained in an advertisement of 1770 about the Hunter:14

DROVE on SHORE, near MARGATE,

THE Ship HUNTER, Capt Alexander Cristall, Commander; and as the said ship is upon the main, and therefore not deemed a wreck, this to give notice that no persons shall attempt to board the said ship, to secure any part of the cargo, without an order from the captain; and all persons that have taken up any of the cargo of the said ship, are desired to deliver the same to Mr Francis Cobb, of this place, and they shall be paid the proper salvage. — lf Information should be given against persons who possess any part the said cargo, they shall receive half the value of the goods, and the possessor prosecuted with the utmost rigour of the law.

ALEXANDER CRISTALL. Margate, December 27, 1770.

In January 1771 a public sale was advertised at the White Hart, of ‘twenty eight silver and metal watches, saved out of the Ship Hunter’.15

Many of Margate’s poor would have considered wreckage or cargo washed ashore from a wrecked ship to be a ‘harvest of the sea,’ waiting to be gleaned. Owners of the ships and cargo would, of course, have a different view, believing that the property was theirs, even if they were willing to pay for the work done in collecting it and keeping it safe. A case arose in 1756:16

Whereas a large quantity of bees wax was drove on shore or taken up floating out of the vessel lost the 26th of February near the North Foreland, on Fairness near Margate, and great part of the said wax not being delivered to the Proprietors, but concealed or stolen, Notice is now given, that if any person or persons who has so concealed the same, that they forthwith deliver it to Mr Hayward, the Master of the said vessel, at Margate, and they shall be reasonably satisfied; and that if any other person that said wax may have been offer’d for Sale, or bought any of the said wax, will deliver the same either to the said Master, or to Mr Brooke at Margate, or give any Information who has bought any, they shall also be reasonably encouraged. Any person not delivering, and being informed against, will be prosecuted as the law in such case directs.

In February 1773 a ship on the way from Gottenburg to Cork, laden with pickled herrings, grounded on Margate sands.17 The Deputy, Francis Cobb, placed a warning notice in the Kentish Gazette that ‘numbers of boats have been on board the vessel and carried away part of her cargo, and cut and carried away some of the planks, beams, mast and materials. . .’ He gave notice ‘to anyone with part of the vessel or cargo to deliver them to Mr Francis Cobb, agent for the same, by whom they will be paid the proper salvage’ and warned ‘whoever shall, after this public notice, be found guilty of such vile practices, as cutting or destroying any part of the said vessel, or embezzling any of the cargo, will be prosecuted, with the utmost severity of the law.’ The advertisement must have worked as in April an advertisement appeared for ‘a large quantity of pickled herrings’ to be sold at Mr Cobb’s Brewhouse in Margate, ‘at 40 herrings for sixpence or 12s the barrel,’ an arrangement aimed to allow the poor of Margate to buy their fill; it was reported that the total number of herrings for sale exceeded 600,000.18 In 1782 100 chests of oranges, saved from the brig Luzitania wrecked on Foreness Rock, were offered for sale at the Fountain Inn by Cobb and Hooper.19 However, the advertisement announcing the sale went on to say: ‘Whereas a great deal of the cargo, which consisted in fruit, cotton, brazil wood &c and some part of the materials of the said brig, has been stolen, and unlawfully run away with, any person, who, within the space of fourteen days from the date hereof, shall think proper to bring any part of the said articles or materials to Messrs Frs. Cobb and Hooper, at Margate, will be entitled to the usual salvage; but if, after the expiration of that time, any such goods or materials, shall be found in the possession of any person whomsoever, he may expect to be prosecuted as the law directs.’ A similar warning was also issued in 1782 about a load of wood from another stranded ship:88

Whereas it is apprehended, that great parts of the FUSTICK WOOD [a wood used in dyeing], which was on board the ship Emperor, Captain William Wilson, from Jamaica, and lately stranded on the Mouse Sand, has been landed, carried off, and secreted; this is to inform all persons who have been, or may be concerned, or have any knowledge in the carrying off, or secreting any of the said wood, they may receive a reward, or salvage, of one half the net proceeds of any quantity they shall bring and deliver unto Messrs Cobb and Co., at Margate, Kent, or Mr William Purdy, Broker, No 86 Great Tower St., London; or whomsoever shall or will inform the aforesaid gentlemen where such wood is concealed, or may be found and recovered, they shall be entitled to the same reward, or salvage, of one half the net proceeds — but if afterwards any person, or persons, are found out concealing or secreting, or having such wood in their custody, they will be prosecuted to the utmost rigour of the law.

Ten years later the harvest from the sea was bags of cotton:20

Reward for Salvage

Whereas the Brig HOPE, Capt. Thomas Linthorne, unfortunately ran ashore on Margate Sands last Friday morning, on her passage from Lisbon to London, and laden with cotton, skins, wine, tobacco, and other sorts of merchandise — And as some of the bags of cotton in particular have been drove on shore, and taken up by persons unknown along the coast, this is to give public notice to all such persons, as well as those who may direct save any part of the said vessel’s cargo or material, to deliver them to the warehouse of Stephen Basset, merchant, Margate, which will entitle them to salvage, but if any part of the said vessels’ cargo or materials are found to be embezzled, the owners are determined to prosecute to the utmost rigour of the law.

T. Linthorne, Master.

The advertisement seems to have worked, since a few weeks later an auction was held at the King’s Head Inn of various items saved from the brig, including ‘300 bales and scroons of Brazil cotton, 10,000 lamb skins in wool, and 300 dog fish skins’.21 In 1804 it was bundles of linen that floated ashore at Margate, from the Hambro shipwreck.22 Again, the public was warned that any bundles recovered from the beach should be handed in, and, in fact, 200 pieces of linen sheeting from the ship were sold at auction a month later.23

For whatever reason these types of advertisement had largely disappeared by the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Newspapers were also used to give information and warnings about run-away apprentices. In 1753 a Margate carpenter placed an advertisement warning anyone about employing his run-away:24

Whereas Edmund Terry, carpenter, has absented himself from his Master’s service, Mr John Croft at Margate; this is to desire him to return to his service with speed, and he shall be kindly received. He is a tall young man, about 19 years of age, a dark complexion, wears his own hair, and his right ankle somewhat swelled by a strain. Whoever entertains him, shall be prosecuted according to Law, by me.

John Croft.

A similar advertisement was placed in 1775 by Simon Crouch, a Margate fisherman, offering a reward of two guineas for information about his run-away apprentice William Selby, just 5 feet 4 inches tall, seventeen years old and of ‘fresh colour.’ The advertisement gives interesting details about the clothing choices of a young fisherman at the time: he was wearing ‘a blue jacket, checked shirt, [a] pair of sea boots and round hat’.25 In 1776 Henry Basset, a carpenter of Margate, advertised for information about his run-away apprentice William Kilby. In this case no reward was offered, but Kilby was assured that ‘if he returns to his Master or to his family in Canterbury . . . he will be favourably received.’ He was described as being nineteen, just five feet one inches high, with a fresh complexion, pitted with the small pox, ‘and had on a brown surtout coat’.26 Capt. John Bow’s attitude to his run-away apprentice John White was very different; in 1784 he promised a reward of one guinea to ‘whoever will apprehend him, so that he may be brought to justice’.27

Husbands placed advertisements warning about their wives, for whom they were financially responsible. In 1778 Isaac Covell advertised in the Kentish Gazette: ‘This is to forewarn all persons not to trust Lieutenant Isaac Covell’s wife, on any account whatsoever; for he is determined never to pay any debts that she shall contract on his account from this time’.28 We can only guess what lay behind this advertisement but a less mysterious case was that of Henry Warren, a Mariner of Margate, who advertised in 1751 that his wife, Elizabeth Warren, had eloped and that ‘this is to warn all persons not to trust her on his account, for he will not pay any debts of her contracting’.29 Not only the relatively affluent would place such advertisements ; in 1807 James Barnett, an illiterate labourer placed a warning about his wife:30

Margate, Nov. 20 1807

This is to forewarn all persons not to trust Elizabeth Barnett, wife of James Barnett, labourer, from the date hereof, she having eloped from her said husband, and therefore he will not pay any debts she may contract.

His mark X. JAMES BARNETT

These advertisements sometimes hint at a very tangled tale. In 1770, George Hubbard placed an advertisement in the Kentish Gazette reporting that his wife has run off with a Margate schoolmaster, Thomas Coleman:31

ELOPEMENT

Whereas ELIZABETH HUBBARD, wife of GEORGE HUBBARD, of Margate, in the County of KENT, Mariner, hath lately eloped with THOMAS COLEMAN, of Margate, Schoolmaster.

These are to desire all Persons not to entrust or harbour her, as disagreeable consequences may ensue.

GEORGE HUBBARD.

A few weeks later Thomas Coleman published a letter in the Kentish Gazette denying the truth of Hubbard’s claim:32

To the Printers of the Kentish Gazette.

Sirs, As your Paper has twice published a false, and injurious advertisement, of my going off with the wife of George Hubbard, I desire the following also may be twice inserted, as a part of that justice I am obliged to do to my injured character.

I am a Schoolmaster, and usually take the opportunity of holidays for business in London and other places. During my late absence, a scandalous Advertisement appeared against me, signed George Hubbard. The true state of the case I now lay before the Public.

George Hubbard is one I have done every act of kindness to that lay in my power. Among other things I lately made interest, and procured him the use of a new boat, which cost above £100. But he soon gave himself up again to drink, squandered away what he earned, and left his wife and children destitute.

Sometime afterwards, he came at night to my house, broke the windows, threatened my life, and made several attempts to break open the door. This was because his wife had hid some of the household goods, which he threatened to destroy, and falsely suspected they were lodged with me for safety.

Upon this I took out a warrant, but left him at large for about three months, hoping for his reformation. But after committing several fresh acts of audacious and dangerous disturbances, he was sent to prison.

But getting some persons to credit the wild, ridiculous account of my taking away his house, wife and goods, they gave him bail.

His wife usually going to London once or twice a year, was there at this time, buying shop goods, private friends giving her this assistance, as the only mean of providing for herself and family. And he being now at large, returned in her absence, turned the children, and the person that looked after them, entirely out of doors, sold off what found, as he saw good, drank and rioted as before and out of malicious revenge, published a scurrilous libel. I solemnly appeal to God for the truth of what I allege, and assure the public I never did the least injury to Hubbard, and I defy him to prove the contrary. I know that his own conscience testifies against him: and he knows that I have living witness that, in his sober intervals, he has often acquitted me, and taken the whole blame on himself: and that he very lately wept, and owned, "I had been a friend indeed to him: — that what he had spoken against me was false and the effect of liquor: — and that his wife was a virtuous woman, and had always been a good wife."

I now commend my cause into the hand of a Righteous and Almighty Judge; and I pray God my cruel enemy, that his sin may not be laid to his charge. What he has long done against me was first the effect of liquor; afterwards, of taking counsel with wicked men, which at last wrought his spirit up to no less than a kind of madness, and thirst for blood.

May he be a warning to others, not to walk in the counsel of the ungodly, nor break any of the commands of God, lest we should be given over from one sin to another, and perish for ever.

THOMAS COLEMAN.

Margate, May 2 1770.

The Editor of the Kentish Gazette added after the letter:

The day before the sessions, Hubbard confessed that the whole he had said against Mr Coleman was false; and owned he was stirred up to it by his wicked companions; and in particular said that, during his imprisonment in Dover Castle, a certain Attorney had set him on to publish that advertisement.

The same issue of the Kentish Gazette included an advertisement from George Hubbard:32

To the PUBLIC,

WHEREAS I GEORGE HUBBARD of Margate, Mariner, did put a wicked and slanderous advertisement in the Kentish Gazette of April the 21st, 1770, entitled, An Elopement of my Wife, Elizabeth Hubbard, with Thomas Coleman, Schoolmaster: This is to certify, that the same is entirety false; and I do hereby beg Pardon of Mr Coleman, and promise never to do the like again and do acknowledge my wife, Elizabeth Hubbard aforesaid, to be a truly honest, industrious, and virtuous woman, and I have none to blame but myself and wicked counsellors.

Witness my Hand this 3d of May, 1770. GEORGE HUBBARD.

Small infractions against local bye laws were also dealt with as far as possible without going to law. In January 1799 John Paine, Thomas Holness, John Simmons, Edward Ladd, Zechariah Simmons, John Debock, John Drew, George Phillpott and Josiah Skinner were served with summonses to appear before the Mayor of Dover ‘upon complaint against them for driving on the foot pavement within this Town’.33 They appealed to the Margate Commissioners for mitigation and the Commissioners agreed: ‘that upon each of the before named persons paying to the Treasurer seven shillings and sixpence (being two thirds of the penalties incurred by each of them), and two shillings and six pence for the Town Clerk’s charge for each summons, the prosecutions against . . . the said persons . . . shall cease – All the said persons being at the same time informed by the Commissioners present, that in case of any of them being charged with a like offence in future no mitigation of penalty will be allowed to them.’ The case had been brought based on information provided by Stephen Rowe to the Mayor of Dover, and the Commissioners ordered that Rowe should be paid ‘one moiety of the mitigated sums’ as ‘compensation.’

Traffic offences were still a problem in 1811 when the Commissioners fined William Grayling 10s ‘for letting his carriage remain on Market Street, and thereby obstructing the free passage and that such fine be immediately paid.’ Grayling appeared before the Commissioners and ‘confessed that he had been guilty of the offence’ but refused to pay the fine. The Commissioners ‘immediately directed [a Constable] to convey him to the Common Gaol of Dover there to remain pursuant to the Act of Parliament’; Grayling changed his mind and paid the fine.34

If a victim had to go to law, he would, before 1811, be faced with travelling to Dover to present his complaint (called an ‘information’) to the Mayor of Dover or one of the other Jurats, who were the magistrates for Dover and its limbs, although after 1811 he could go to one of the local Cinque Port Magistrates. His complaint would usually be taken down in writing and, if the complaint was serious, this would be done under oath.35 If the magistrate decided that the complaint corresponded to an indictable offence such as a felony or misdemeanour, he would order the accused to be called before him to be examined; he would do this by issuing either a summons or a warrant. For less serious cases, and in cases where the accused was thought unlikely to abscond, he would issue a summons that would simply require the accused to appear before the magistrate at a given time on a given day; the summons would be served on the accused by the Deputy of Margate or by one of his assistants. If the case was more serious the magistrate would issue a warrant ordering the Deputy to apprehend the offender and bring him to the magistrate. Whether by summons or by warrant, the accused would be brought before the magistrate, who would examine the witnesses and hear what the accused had to say in his defence. He would then either discharge the accused, if he thought there was no case to answer, or commit him to prison or release him on bail to appear at the next session.

A few of the original dispositions taken before the Cinque Port Magistrates are preserved in the Kent Archives, often written on standard printed forms. William George Massared made a complaint before two of the Cinque Port Magistrates in 1836:36

Margate, in the liberties of the Cinque Ports — Information and complaint of William George Mussared, fishmonger, taken and made before William Nethersole Esq and the Rev Francis Barrow, two of His Majesty’s Justices of the Peace within and throughout the Liberties of the Cinque Ports 29 July 1836.

Says ‘I reside at the Fishmonger’s shop in Hawley Street, and this morning at a little before three, I heard a noise of some person or persons breaking into the lower part of my house — the shutters of the fish shop — I got up and looked out of my bedroom windows but I saw no one. I dressed myself and went down stairs and into the street and discovered one shutter partly down in a very different manner from the state in which I had left them last night. A dish of shrimps stood on the window close to the opening and the shrimps now [moved] about both inside and outside my house and some were gone.

I neither heard anybody at the time of the breaking the shutter nor saw anybody — the latch of the back door was broken which was [intact] when I went to bed. The two prisoners John Bax and George Kemp were in the public office with the constables the day before the magistrates came to hear this charge. I heard Bax say that George Kemp pulled the shutter down though Box took the shrimps.

Kemp and Bax, both just 10 years old, were charged with breaking into the house of W.G. Mussared, a fish monger, at Margate, and stealing some shrimps.37 They were sentenced at Dover to 14 days imprisonment; the Dover Telegraph reported ‘they appeared to have no friends. A sea-faring man named Wilkens, who said he walked from Margate to speak for Bax, whom he had brought up, promised to take them back after their release.’

In 1836 William Smart, a Margate labourer, made a complaint to William Nethersole about Catherine Scott, a prostitute:36

On Thursday evening last about a ¼ to 2 o’clock I met the prisoner Catherine Scott on the Marine Parade in Margate, she asked me to go with her and I did so, behind Draper’s House upon the Parade. I had in one pocket two pounds six shillings and six pence and ½ a crown in another . . . When we got behind Draper’s House we had connexion together, I gave her a shilling first and then sixpence more. This was before she let me do anything with her. The two pounds six shillings and sixpence was wrapped up in paper, she saw me take the paper out of my waistcoat pocket when I gave her the money. I afterwards felt her hand about my person. Immediately after we had been together, she went away and in a minute or two I found that my money (two pounds five shillings) had been taken out of my pocket. We did not lie down and I am quite sure the money could not have got out of my pocket by accident . . . I afterwards found out where she lived and went to her house last night. I asked her for the money. She said she had never seen me and was not at the place at the time.

Another labourer, Henry Osborn, gave information as a witness, and claimed that he saw William Smart talking to Catherine Scott and afterwards ‘I saw them go up at the back of Draper’s House on the Parade’. Nethersole decided to commit Catherine Scott to trial at Dover.

Some complaints made clear how much time was required to collect enough evidence to convince a Magistrate that there was a case against a suspect. Solomon Johnson, a coach house keeper, had this problem when, in 1828, he presented his case against William Kirby Moat and John Larkins to John Friend, another of the Cinque Port Magistrates.38 The information said:

For many weeks past he [Solomon Johnson] has strongly suspected that the food intended for his horses at his coach stables in Margate has been stolen . . . and that in consequence thereof he has endeavoured to set a watch upon William Kirby Moat, alias Berry, his ostler and also upon John Larkins who keeps Livery Stables in Margate and with whom the said Moat is intimate — That about a fortnight ago he caused some black and white oats to be mixed and he afterwards by the assistance of a person whom he had appointed to watch was confirmed in his suspicion that such mixed oats found their way into Larkins’ Corn Bin — That he in order to ascertain the matter with certainty stained a quantity of oats with a dye from logwood and vinegar for the purpose of mixing with some black and white oats and delivered them in charge to his wife to get them mixed and within 3 days afterwards he saw a quantity of oats amounting in bulk to 6 or 7 quarters in his loft mixed according to his directions — On Friday last he went to the Livery Stables of the said John Larkins and in a corn bin there he found a bushel and a half of oats with which a part of the stained oats were mixed.

Johnson went on to state that the only servants who had care of his corn were John Wattler, George Pain and William Kirby Moat, and that on Saturday evening he had received a message from George Pain saying that Moat wished to see him. When he met Moat, Moat began to cry and said “I am very sorry for what’s happened,” . . . and “I own that I am guilty, I stole the corn and took it to Larkins — in two instances Larkins has fetched it — once he fetched it with his own carriage and once he fetched it away upon his back — Larkins agreed to give me half a crown a bushel”

Johnson’s case was backed up by Thomas Dowson and John Bristow, two of the constables of Margate:

On Friday noon last they went to the Livery Stables of John Larkins in Margate by the desire of Solomon Johnson to search for some stolen oats which the said Johnson told them were mixed black and white and some stained ones. They saw the prisoner Larkins and told him their business — they then opened his corn bin which was unlocked and there found a quantity of mixed oats, a sample of which is produced at the time of taking this examination — [it] corresponds with the description of oats which [the constables] had previously received from Johnson. Johnson was then fetched to the premises, who immediately identified the oats as being his.

All of Johnson’s hard work paid off; Larkins and Moat were apprehended and ‘lodged in the cage’ and then taken before the Magistrates, who committed them to Dover for trial at the next Sessions.39

If a magistrate was convinced that there was a case to be answered, he would issue a summons or warrant to the Deputy or sub-Deputy at Margate, to arrange for the suspect to be brought to Dover so that he could examine him. A few early summons and warrants issued by the Dover magistrates also exist in the Kent Archives and two examples will show the form that these took.40 In 1786 the Mayor of Dover wrote to the Deputy, Francis Cobb and the Sub-Deputy, Thomas Gore: ‘Mary Hughes, widow, late servant to John Mitchener, Inn Keeper, hath made information and complaint . . . she agreed with Mary the wife of John Mitchener to serve him in the capacity of cook by the week commencing 20 September, for which she was to be paid wages at the rate of 8s by the week.’ According to Mary Hughes she continued working until 12 May ‘when a dispute arose between her and the said John Mitchener in which he was guilty of much abuse to her and declared that if she did not go out of the house he would kick her out whereupon the said Mary Hughes demanded the arrears of wages due to her amounting to £8 which the said John Mitchener refused to pay and hath not yet paid.’ The Mayor requested the Deputy or Sub-Deputy to serve a summons on John Mitchener ‘to appear before me at the Guildhall [in Dover] on Friday.’

In April 1801 a warrant was sent to Francis Cobb and Thomas Gore for the arrest of John Brisley:40

Francis Cobb the younger of Margate — made information and complaint upon oath before William King Deputy Mayor and JP of Dover — that divers quantity of beer, coals and grain have lately been feloniously stolen . . . from out of the Brewhouse and yard belonging to and in the occupation of the said Francis Cobb the younger and Francis Cobb the Elder his co-partner at Margate . . . and he has probable cause to suspect and doth suspect that John Bayley, John Brisley and William Knight, all of Margate, labourers did so feloniously steal take and carry away the said beer, coals, and grains.

An important part of any successful prosecution was the collection of sufficient evidence to convince a jury. One way, hopefully rare, was reported in 1800:41

Wednesday last, a servant girl at Margate, who had stolen a banknote of £5 value, on being accused, to prevent detection, swallowed it; after some expostulation she however confessed the fact, and an emetic was administered, without immediate effect. Mr S. Rowe, then present, gave her some warm salt water, but the first draught not operating, the second, to the astonishment of many, produced the note from her stomach without injury.

Sometimes the victim could catch the criminal red-handed. In January 1804 there was a robbery at a house in Westbrook belonging to a Mr Leach.42 Although the house had been unoccupied for some time, it was left with all the bedding and furniture in it, ‘as is the custom with many of the lodging houses in that neighbourhood.’ Someone saw some young women ‘of bad character’ going into the house and informed Mr Hall, the postmaster, who was looking after the house. Hall, together with a friend, went to check on the house and found the doors broken open and two dozen bottles of wine and some bed linen missing. They then ‘heard a footstep, and discovered two . . . ladies locked in a closet, and who at length made their appearance, in part decked with the spoils of their industry — they had lived there sometime, — they had made up the bed furniture into chemises and petticoats [ and drunk the wine] — the two were Mary Hopper and Charlotte Hills — they were secured in prison, and suspicion fell on a third [Elizabeth] Clarke, who was apprehended in St. Peter’s, and taken before F. Cobb, confessed, and all three were committed to Dover gaol for trial.’ At their trial at the Dover Summer Sessions Charlotte Hall was found guilty and sentenced to one month’s imprisonment but Mary Hopper and Elizabeth Clarke were acquitted.43

Often a victim would place an advertisement after a theft or robbery asking for information to help recover the stolen goods and identify the perpetrator. The advertisement could take the form of a handbill, plastered throughout the town, offering a reward for information or could be an advertisement in a local newspaper. In 1754, William Bourn of the Foy-Boat Hotel in Margate placed an advertisement in the Kentish Post reporting that his ‘small wherry, painted with green on the inside’ was ‘lost or taken away’ and offered a reward of half a guinea for information leading to its recovery.44 In 1772 the pigeon house and hen roost of Thomas Reynolds in the Dane was broken into and the fowls taken away. Reynolds promised a reward of five guineas to anyone giving information leading to a conviction.45 In 1795 there was an outbreak of robberies. One night some men broke into a house in Westbrook while the family (Mr Lee’s) were in bed, and stole a quantity of plate to the value of £50; ‘It appears that they took considerable time to effect their purpose, as they selected some plated goods which were intermixed among the silver, and strewed them on the floor as unworthy their notice. – A reward of £20 is offered by Mr Lee for their detection’.46 A few days later twelve silver table spoons were stolen from a room in Benson’s hotel, and several articles of plate were stolen from the parlour of Mr John Rayley. The Kentish Chronicle reported that it was hoped that the thieves would soon be captured ‘as considerable rewards are offered’, but this was not to be.46 A week later there was a further robbery: ‘last Sunday evening, while Mr Sawkins, banker, in Cecil Square, was drinking tea upstairs with his family, some thieves entered the dining room and stripped the side-board of about twenty pounds worth of plate, with which they got off undiscovered’.47

In the days before the motor car, horses were numerous and vulnerable to crime. There were many advertisements offering rewards for the return of horses that had ‘strayed’. Typical of many, Samuel Bloxham, a stable-keeper, offered a 2 guinea reward for information about a ‘black nag-tail saddle gelding’ that had strayed from out of the Brooks; to help identify the horse, it was described as having ‘his ears wide apart, and has had a cut on one eye-lid, which rather hangs down’.48 Those hiring out horses were particularly at risk of loss. In 1787 Robert Salter reported that a man ‘who had every appearance of a gentleman’ hired a horse from him on a Sunday, ‘to take a morning airing,’ and although he agreed to return the horse by dinner time, he did not.49 Salter described the man as ‘about 30, his hair tied, about 5 feet 10 — had a snuff-coloured coat, a scotch plaid waistcoat, and a new pair of boots.’ Salter was more interested in the horse than in the man and offered a guinea reward to anyone giving information leading to the return of the horse. In 1797 John Rette had a similar problem: ‘If the person who hired a horse and one horse chaise or whisky, of Mr John Rette, of Margate, on the second day of July inst., to go to Dartford, and to return in four days, does not immediately return the same horse and chaise, every means which the law directs, will be taken for recovery of the same’.50

Other victims of crime were more interested in punishing the criminal than in the return of their stolen goods. On the night of 13 October 1784, the house of the Rev Mr Wells in Church Field was broken into by two or more men who collected up a large quantity of linen and other articles to take away ‘but were prevented carrying them off by the Family’s being seasonably alarmed’.51 Wells discovered one of the men on the staircase near his bedchamber and struck him ‘a violent blow to the right side of the head with a candlestick,’ chased him through two rooms and then had another scuffle with him before he escaped. Despite the fact that nothing was actually stolen, Wells placed an advertisement in the Kentish Gazette of October 16 offering a reward of £10 ‘to anyone discovering the offenders so they may be convicted’.51 To help identify the intruders Wells reported that one of them ‘had on a Carter’s frock, and is a middle sized, active man.’ Despite all the potential clues, the wrong man became a suspect. In the 27 October issue of the Kentish Gazette, an advertisement was placed by Richard Sandlands, a hairdresser in Ramsgate:52

To the public. Some villains having broken into the House of the Rev Mr Wells . . . and suspicions having fallen on me, as injurious as they are unjust, through the malicious insinuations of some person or persons unknown . . . I think it is but justice to . . . make it known that Mr Wells, after the most thorough investigation, is perfectly and entirely satisfied of my innocence.

An earlier case of rumours quashed by an advertisement occurred in 1771:53

Whereas RICHARD STOKES, servant to Mr RUSSELL, and WILLIAM BEALE, servant to Mr SACKETT, farmers, in the Isle of Thanet, did on the 28th day of January last, sell a small quantity of old silver to Mr THOMAS ROWE, at Margate, and the silver being missed soon after they were gone from the shop, it was conjectured they took it away with them, which has occasioned many reports prejudicial to the young men’s characters — in justification whereof, I hereby inform public, that the above mentioned silver has since been found, and has proved such reports to be groundless and without foundation.

Margate, Witness, HILLS ROWE. Feb. 8, 1771.

The difficulty in obtaining evidence sufficient to mount a successful prosecution led to the practice of allowing accomplices to turn King’s evidence, impeaching their partners in crime to gain immunity from prosecution for themselves, often, at the same time, gaining a handsome financial reward. However distasteful the practice, it was often the only way to obtain the evidence necessary to gain a conviction. Turning King’s evidence did though carry a risk; if several offenders all made confessions, only the first one to do so would obtain immunity and the others could find their confessions used against them in court.2,5 In 1794, the Proprietors of the Theatre Royal issued a poster reporting that the theatre had been broken into on the night of 1 August and that banknotes, and gold and silver coins had been stolen from a desk, to a value of about £34.54 They offered a reward of £20 to be paid upon conviction to ‘Whoever will give Information so that the Person or Persons guilty of the said ROBBERY may be brought to Justice.’ They added ‘any Accomplice giving such Information, and appearing as Evidence upon the Prosecution shall be entitled to the like REWARD.’

Cases in Margate where King’s evidence is known to have led to a successful conviction include that of a robbery where a large number of silk stockings and gloves were stolen from Silver’s shop.55-57 Three men were arrested for the crime, Henry Jackson, James Jordan, and John Hind. They were taken to Dover where Hind turned King’s evidence and the three were committed to Dover gaol to wait until the next Court of General Sessions. In September Henry Jackson was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to transportation for seven years; James Jordan’s fate was not reported. The outcome was similar for the men who broke into the storehouse of Messrs Cobb, Hooper, and Co. near Cobb’s Brewhouse in Margate, and stole six quarter chests of tea, part of the cargo of an East Indiaman.58,59 The company placed an advertisement in the Kentish Gazette offering a reward of £50 to anyone giving information that would lead to a conviction. Just a few days later William Haywood was committed to Dover gaol, having turned King’s evidence and impeached six others; also committed to Dover gaol was Richard Love, accused of buying some of the stolen tea. But not everyone approved of a system which could end up rewarding a convicted felon for his crime. In 1775 John Cowper, Surveyor in the service of the Customs at Margate, placed an advertisement offering a reward of £10 for information about the man who had one night ‘maliciously cut to pieces the sails belonging to the boat employed under [his] care’ and had also stolen his anchor, but, Cowper added, the reward would not be paid ‘to the person who actually committed the said offences’.60

Advertisements were also used to help capture suspects in serious crimes. On the morning of Sunday 9 April 1786 John Ancell, a poor farm labourer, was found clubbed to death in a field adjoining Drapers Almshouses in Margate.61,62 The previous evening he had been drinking heavily in Margate and had set out at about a quarter to eleven to walk home along the road to St. Peter’s. Suspicion for his death fell immediately on one Charles Twyman since it was known that there was bad feeling between Ancell and Twyman, and Twyman had been heard publicly threatening to take revenge on Ancell. Even more damning, Twyman had been seen leaving Margate on horseback, along the St. Peter’s Road, at the time that Ancell had set out for home. Riding pillion with Twyman had been a boy and although Twyman could not be found, the boy, who lived with Twyman, was brought in for questioning by Deputy Cobb on Sunday afternoon. For a long time the boy denied all knowledge of the murder and ‘though only twelve years of age, kept to one account so artfully, that it was with the greatest difficulty he was made to confess the truth’ but finally he admitted that Twyman had killed Ancell and gave the following account:

Twyman was on horseback, and overtook the deceased about eleven o’clock on Saturday night, a short distance from Margate church yard, on the road to Draper’s; that he first attempted to take a bag from Ancell, and told him that he was an excise officer; but Ancell, knowing Twyman, called him by his name, and refused to give up his property; on this a scuffle ensued, and Twyman knocked Ancell down by a blow on the head with a stout club stick. Ancell recovering a little, got away as far as Draper’s, near half a mile from the place where he was first struck, but Twyman then came up with Ancell again, and knocked him down a second time. After this the poor wretch got on his knees and begged for mercy. Twyman dismounted, shook hands, and promised he would not strike him any more, but almost at the same instant the blood thirsty villain gave the unhappy man several violent blows on his head, which fractured his skull, then made him (the boy) strike the deceased several times, while he was bleeding on the ground, and afterwards Twyman walked his horse two or three times over the body.

Twyman was charged with murder at a Coroner’s inquest but efforts to find him failed. It was thought that he was in hiding somewhere on the Isle of Thanet and he was almost caught on Monday 10 April ‘in a house at Northdown near Margate which home was searched about half an hour after Twyman had left it’.63 An advertisement was then placed in the Kentish Gazette offering a reward of five guineas to ‘whoever shall apprehend Charles Twyman or give notice to Mr Cobb, Deputy of Margate, so that [he] may be apprehended and brought to justice’.64 Twyman was described as being ‘about 28 or 30 years of age, about five foot five or six inches high, thick set, of a swarthy complexion, and wears his own dark hair loose behind.’ The advertisement obviously failed since a few weeks later a fresh advertisement appeared with the reward increased to 20 guineas.65 A Sandwich man, Giles Gimber, was committed to Sandwich gaol for ‘having received, aided and comforted’ Twyman, but Twyman was never caught.66 The Kentish Gazette published a rumour circulating at Dover that Twyman had been seen in France ‘but what foundation there is for it we cannot learn and . . . we therefore do not give it our readers as truth, though not unlikely’.66

Even when the victim had sufficient evidence, the expense and inconvenience of going to trial could be a strong disincentive. This is illustrated in a case of 1824 when the victim could not be bothered to attend the Dover sessions when his case was coming on; the report in the Kent Herald also gives details of how the court was run:67

DOVER SESSIONS. ROBBERY OF GARNER’S HOUSE AT MARGATE

Thomas Appleby Walne, was indicted for breaking into the dwelling house of William Garner, at Margate, on the night of the 2d of September last, and stealing various articles of jewellery therefrom.

There was a second indictment against the prisoner, for a like offence in stealing in the same dwelling house, one gold seal, the property of Wm. Custins, shopman to Mr Garner.

The Grand Jury returned both true Bills— andtheprisoner was arraigned at the bar, and the trial about to proceed, when it was discovered that Mr Garner, who keeps the Library at Margate, who was robbed, and who was prosecutor in the one case, and a material witness in the other, was absent! It also appeared that by some unaccountable neglect, the stolen property had been given back into the hands of Garner, instead of the constable, into whose custody it ought to have been entrusted. As neither Garner nor the stolen property was present, it was impossible for the trial to proceed.

The Recorder directed Mr Garner to be called three times, — which was done, and upon his not appearing, the Recorder said :—

"Gentlemen of the Jury, Mr Garner's not being here is a most shameful and scandalous thing. I am afraid it is impossible to do anything without the evidence of Mr Garner, and I am very sorry for it, as we shall now be obliged to turn this man loose upon the public."

Here the Recorder again asked Wm. Custins if he had seen the seal since the robbery. He answered “yes”. In whose possession? "In Mr. Garner's possession." Do you know how he came by it? "I do not." Mr. Gamer is not here I believe. — “I believe he is not, Sir."

Recorder, —Then, Gentlemen, it seems the prisoner must he acquitted, for want of evidence; but it is most scandalous conduct on behalf of the prosecutor. I have ordered his recognizence (£40) to be estreated — and the consequences will visit him!

In rare cases, for very serious crimes, the Parish Officers could fund a prosecution, as in the sad case of Sarah Hayward in 1802:68

Dover — This day the general Sessions of the Peace for this town, and its limbs and precincts, were holden at the Guildhall; at which Thomas Brown a baker at Margate, was indicted for a rape on Sarah Hayward, a girl of the age of twelve years, the daughter of a brewer's servant in the same town. Mr Harvey, as counsel for the prosecution, opened the case in a very pathetic address to the jury on the atrocity of the crime, stating that the present action was brought, without the least degree of private resentment, or malice, by the Parish Officers of St. John, purely for the sake of public justice; the poverty of the child's parents being such as to preclude them from prosecuting the offender. After the Recorder had summed up the evidence, the Jury retired for near an hour, and returned with a verdict of Guilty of the Attempt. The Recorder informed them they must either find the prisoner guilty of the fact, or acquit him; they then returned a verdict of Not Guilty! The trial lasted five hours.

Many towns had local prosecution associations to help share the expenses involved in the pursuit and prosecution of offenders. Tradesmen paid a subscription to join the association and the association offered rewards for the conviction of those who committed offences against their members. Margate established a Prosecution Association in 1773, following a number of house breakings:69

The alarming progress of house breaking has given rise to an association at Margate, the intention of which is, to prevent offenders escaping justice on account of the expense of prosecution; every member engages to pay a proportionable part of the charges attending the trial and conviction of any person, committed for burglary or theft, so far as it relates to the property of any of the subscribers; the instrument for this purpose is left at Mr Hall’s Circulating Library, where all persons may have an opportunity of perusing it, and subscribing, if agreeable.

In what was probably a typical case, the association placed an advertisement in the Kentish Gazette in 1795 reporting that the storehouse of Robert Salter, a member of the Association, had been broken into and some groceries stolen.70 A reward of 20 guineas was offered ‘to any person or persons who shall discover or apprehend any one or more of the said offenders — To be paid by the Chairman of the Association on conviction.’ It seems likely that this association was abandoned at some time, as an advertisement appeared in 1804 for an ‘Association for the Prosecution of Offences committed within the Isle of Thanet’, with three of Margate’s most prominent men, Francis Cobb, Daniel Jarvis and Edward Boys, as trustees:71

Association for the Prosecution of Offences committed within the Isle of Thanet.

Town-Hall, Margate, Nov. 6 1804.

At a General Meeting held here this day, the following resolutions were unanimously agreed to:—

That a fund be established for the prosecution of offences committed within the Isle of Thanet, against the property of any the Subscribers.

That, for the improvement of the fund, the monies shall be regularly placed out at interest, in the names of the three Trustees for the time being. — In case of vacancies, Trustees to be supplied by ballot at the next General Meeting.

That a Committee be appointed, to consist of the three Trustees, and six other Members of the Society, to be chosen annually by ballot.

That for the choice of such committee, and for the general purposes of the Association, a meeting be holden annually at this place, the first Tuesday in the month of November, at eleven o'clock, in the forenoon.

That any Member of this Society may propose a new Member; the amount of whose subscription shall be determined at a General Meeting, to be convened for the purpose, within one month after an intimation to the Secretary. — No Subscription to be more than Ten Guineas, nor less than Two.

That a Secretary be appointed at a salary of two Guineas per annum.

That all applications, for the protection of this Association, be first made to the Chairman of the Committee for the time being.

That, for increasing the fund, each Subscriber shall at every Annual Meeting contribute one shilling upon each guinea of his original subscription, until the fund shall amount to three hundred pounds.

That if any Member shall neglect to pay such additional Annual Subscription, at the General Annual Meeting, the Secretary shall make personal application for the same, for which he shall receive six-pence; and in case of neglect of payment for one month afterwards, the Member shall not be entitled to any farther benefit from this Society.

That all prosecutions shall be conducted under the immediate superintendence and advice of a majority of the committee.

That, in case of prosecutions, no larger sum than one guinea shall be allowed for a journey to Dover for any one person.

That no member shall be called upon for more than his original Subscription, and the annual and additional Subscription.

That, Mr FRANCIS COBB, Mr DANIEL JARVIS, and Mr EDWARD BOYS be appointed Trustees.

That, Mr Edward Pilcher, Mr John Sackett, Mr Edward Taddy, Mr Sackett Wood, Mr John Brooman, and Mr Stephen Mummery be appointed Members of the Committee for the ensuing year.

And that Mr James Warren be appointed Secretary to this Association.

N. B. At this meeting 25 persons became Members of this Society, and subscribed the amount of £135 9s.

|

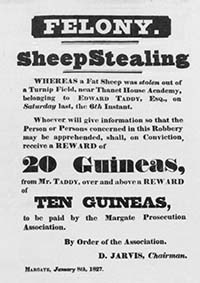

Figure 1. Sheep stealing poster, issued by the Margate Prosecution Association in 1827. |

The Margate Prosecution Association was still active in 1827, now with Daniel Jarvis as Chairman, when a poster was printed offering a reward of 20 guineas for the conviction of those concerned in stealing ‘a fat sheep’ from a turnip field near Thanet House Academy.72 It was, however, about this time that criticisms started to appear about how the Association was being run by Daniel Jarvis. The Kentish Mercury was actively campaigned for reform in Margate, publishing numerous examples of what it considered the ‘shameless waste of the Margate ratepayers’ money by the Commissioners of Paving and Lighting’. Two cases they lighted on concerned the costs of prosecuting Dr Jarvis’s man servant, Stephen Norris, for felony and the costs of an indictment against Lavinia Mummery for a nuisance.73 At the Dover Sessions in October 1831 Stephen Norris, 22, was convicted of stealing a water colour painting valued at five shillings, and a Cambric handkerchief also valued at five shillings, from his ‘master and employer,’ Daniel Jarvis;74 the water colour was reported to be a picture of a rat.75 Norris was found guilty and sentenced to transportation for 14 years.74 The case against Lavinia Mummery, ‘a lady of property’ living in Margate, was brought by the Margate Commissioners for a nuisance concerning a small piece of waste ground she owned in Margate; the case was held over to the next Sessions held in February 1832. The background to this case is strange and obscure. According to a letter from John Boys, although the indictment against Mrs Mummery was carried on in the name of the Margate Commissioners, ‘it is wholly dismissed by all the respectable part of the Commissioners as against her’.76 Boys pointed out that ‘Mr Mummery must be possessed of from £15,000 to £20,000 and you will be surprised to hear that your Bench Warrant was executed upon her, so uncourtiously that she was brought by the Constables like a felon to the Office to be bailed and the Magistrates could not refrain from expressing themselves strongly on the occasion; but the Constables said they had received their orders to execute the warrant strongly.’

The total cost of the witnesses for these two cases was £29 7s 1d, of which Dr Jarvis charged £19 6s 1d to the Margate Prosecution Association with the remaining £10 1s being paid by the Margate Commissioners. This included his own expenses of £15 14s, made up of £10 10s for loss of his time, £5 4s for the use of his carriage, and £4 1s for his ‘tavern expenses.’ Another witness, William Edmunds, received £3 3s for the loss of his time and £1 6s for the use of his carriage, and three other witnesses, Mr S. S. Chancellor, Mrs. M’Carthy and Ann Rooffs were paid together £1 6s 1d, and Bristow, one of the Margate constables, 19s 6d. The final cost was £2 17s 6d paid to Hughes for a barouche to take these witnesses to Dover.73

Similar costs were incurred at the Dover Sessions of February 1832, at which the case against Mrs Mummery was considered. At the same sessions an indictment was tried against John Grant, arising out of a vestry squabble between John Grant, a ‘gentleman of fortune residing in [Margate]’ and Dr Jarvis, which culminated in Grant sending Jarvis a letter inciting him to fight a duel.77,78 Mrs Mummery was found guilty and the court ordered her to enter into a recognizance of £40 to appear and receive judgement when called upon, and John Grant was also found guilty and fined £50 with sureties of £1000 to keep the peace for a year.77 Dr Jarvis’s costs this time included £15 15s for the loss of his time, £5 4s for the use of his carriage and £9 7s 1d for his ‘tavern expenses.’ William Edmunds received £3 3s for the loss of his time and 14s for expenses. Two other witnesses, Mr Goodale and Mr Baldry, each received 10s 6d for the loss of their time and 23s 6d for expenses. This time Dr Jarvis charged £10 2s 6d to the Margate Prosecution Association and £29 18s 7d to the Margate Commissioners.73 The implication of the Kentish Mercury report is that Jarvis and Edmunds in particular were rather well rewarded for their efforts and that it was not obvious that the average Margate inhabitant had got much benefit from the costs covered by the Margate Commissioners. Perhaps the members of the Margate Prosecution Association were also less than pleased; by 1836 it was reported that, although there were two prosecution associations covering the Thanet Division of Dover, ‘neither [were] in a flourishing condition as to the number of members’.79 Nevertheless, it seems that the Margate Prosecution Society was still active in 1857:80

Petty Sessions, Wednesday.— Before W. T. Gilder, T. Blackburn, and G. E. Hannam, Esqrs. — Elias Mansfield, 14, E. Jones, 15, Florence Sullivan, 15, and Cornelius Sullivan, 12, were charged, at the instance of the Margate Prosecution Society, with cutting and destroying turnips . . . , the property of I. Synford, Esq., of Nash Court. From the evidence of Andrew Webb, Mr. Synford’s bailiff, it appeared that at about three o’clock on Tuesday afternoon he saw five boys cutting turnips and filling sacks with them. Witness gave them into custody. Mr. Synford said that for the last three months he had been plundered to a considerable extent; he therefore should press for a conviction against the three eldest, who were sentenced to 21 days’ hard labour; the youngest was discharged.

Cases that actually came to trial at the Court of General Sessions at Dover were originally heard in the Guildhall, in a large upper room used both for council meetings and as a court room; an adjoining room was used as a jury room, the space below being occupied by market stalls. In 1834 the corporation of Dover decided that the Guildhall had become too cramped for their needs. As a replacement they purchased a larger building in the Market Place, the Maison Dieu, a charitable foundation of 1221; the fourteenth century chapel was converted into a courtroom, with a number of vaulted brick cells below.81 The Municipal Reform Act of 1835 brought an end to Dover’s Court of General Sessions and Gaol delivery, to be replaced by a new court, the borough Quarter Sessions. Even after Margate became a borough in 1857 and appointed its own justices, prisoners committed by the Margate justices had to be sent to Dover to be tried at the Dover Quarter Sessions; this continued until Margate was awarded its own Quarter Sessions in 1870.

Finally, debtors were treated differently from those accused of felonies or misdemeanors. The treatment of debt in English law relied on the convention that debt itself was not a crime and that a debtor was not a criminal; debtors were not locked up as a punishment but as an incentive to pay off their debts. By the eighteenth century debtors were dealt with at one of three levels; bankruptcy, insolvency, and small debt litigation.82 Merchants and traders owing large sums of money were declared bankrupt, allowing them to avoid imprisonment. Bankrupts could be discharged from bankruptcy by putting up their goods for sale and paying a dividend (a proportion of their debts) to their creditors. Those owing smaller sums of money fell under the remit of the insolvency law. Creditors of an insolvent debtor could go to court and obtain the power to arrest the debtor. If the debtor could not obtain bail, they would be committed to prison to await trial. A creditor who had proved their case at the trial then had two options. One was to seize the ‘moveable chattels’ of the debtor and sell them at auction to pay off the debt. The other was to detain the debtor in prison until the debt had been paid off. Finally, a debtor who owed only small sums was dealt with at local courts of request where a judge could order immediate payment of the debt or payment in a series of instalments. A small claims court of this type was established in Margate in 1807 to recover debts under £5 in Margate, Birchington or St. Peter’s.83 The court met in Margate at least once a month and the first Commissioners making up the court included the mayor and jurats of Dover, the local justices of the peace, and 113 other inhabitants of Thanet, including the Deputy Francis Cobb. All remaining civil cases were removed from the jurisdiction of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports by the Cinque Ports Act of 185584, following which civil cases were heard by the county magistrates at Maidstone.

References

1. D. Hay and F. Snyder, F., Policing and Prosecution in England 1750-1850, Oxford University Press, 1989.

2. J. M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England 1600-1800, Princeton University Press, 1986.

3. The Times, December 5 1785.

4. Clive Emsley, Crime and Society in England 1750-1900, Longman, London, 1987.

5. Peter King, Crime, Justice and Discretion in England 1740-1820, Oxford University Press, 2000.

6. Kentish Post, March 30 1763.

7. Kentish Post, October 5 1765.

8. Kentish Chronicle, May 17 1791.

9. Kentish Gazette, September 23 1808.

10. Kentish Gazette, September 13 1769.

11. Kentish Gazette, October 24 1797.

12. Canterbury Journal, May 9 1786.

13. Canterbury Journal, August 15 1774.

14. Kentish Gazette, December 25 1770.

15. Kentish Gazette, January 19 1771.

16. Kentish Post, March 6 1756.

17. Kentish Gazette, February 13 1773.

18. Kentish Gazette, April 3 1773.

19. Kentish Gazette, February 16 1782.

20. Kentish Gazette, March 20 1792.

21. Kentish Gazette, March 30, 1792.

22. Kentish Gazette, July 17 1804.

23. Kentish Gazette, August 21 1804.

24. Kentish Post, July 28 1753.

25. Kentish Gazette, November 8 1775.

26. Kentish Gazette, February 17 1776.

27. Kentish Gazette, July 10 1784.

28. Kentish Gazette, July 8 1778.

29. Kentish Post, April 27 1751.

30. Kentish Gazette, November 20 1807.

31. Kentish Gazette, April 17 1770.

32. Kentish Gazette, May 5 1771.

33. Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners. Volume 3, 22 January 1794 to 15 December 1802, Manuscript, Margate Library.

34. Edward White, Extracts from the minutes of the Margate Commissioners Book 5, 29 May 1809 to 27 December 1815, Manuscript, Margate Library.

35. John Frederick Archbold, The Justice of the Peace and Parish Officer, Volume 1, 1840.

36. Kent Archives Do/JQ/d1, Dover Assizes, 1836.

37. Dover Telegraph, August 13 1836.

38. Kent Archives Do/JS/d11, Informations etc. before the Cinque Port Justices 1828-1836.

39. Kentish Gazette, March 25 1828.

40. Kent Archives U1453 O37, Miscellaneous Session Papers.

41. Kentish Gazette, August 19 1800.

42. Kentish Chronicle, January 31 1804.

43. Kentish Chronicle, July 20 1804.

44. Kentish Post, July 8 1754.

45. Kentish Gazette, January 7 1772.

46. Kentish Chronicle, September 8 1795.

47. Kentish Chronicle, September 18 1795.

48. Kentish Gazette, September 19 1794.

49. Kentish Gazette, May 20 1787.

50. Kentish Gazette, July 18 1797.

51. Kentish Gazette, October 16, 1784.

52. Kentish Gazette, October 27 1784.

53. Kentish Gazette, February 9 1771.

54. National Archives, HO 42/33 f. 23, Letter to Henry Dundas, former Home Secretary, from Joseph Hall.

55. Kentish Gazette, July 21 1773.

56. Kentish Gazette, July 24 1773.

57. Kentish Gazette, September 1 1773.

58. Kentish Gazette, February 1 1788.

59. Kentish Gazette, February 12 1788.

60. Kentish Gazette, February 4 1775.

61. London Chronicle, April 18 1786.

62. General Evening Post, April 20 1786.

63. Canterbury Journal, April 11 1786.

64. Kentish Gazette, April 11 1786.

65. Kentish Gazette, April 21 1786.

66. Kentish Gazette, April 14 1786.

67. Kent Herald, October 28 1824.

68. Kentish Chronicle, October 19 1802.

69. Canterbury Journal, September 21 1773.

70. Kentish Gazette, April 14 1795.

71. Kentish Gazette, November 20, 1804.

72. Poster, Sheep Stealing, Margate Prosecution Society, January 8, 1827.

73. Kentish Mercury, December 16 1837.

74. Kentish Gazette, 27 October 1831.

75. Canterbury Weekly Journal, 28 October 1837.

76. Kent Archives, Do/JS/d10. Dover Sessions 1832.

77. Kent Herald, March 1 1832.

78. Kentish Gazette, February 27 1832.

79. National Archives, HO73/5, Return of Justices of the Isle of Thanet to the Constabulary Force Commission.

80. South Eastern Gazette, February 17 1857.

81. S. P. H. Statham, The history of the town and port of Dover, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1899.

82. Margot C. Finn, The character of credit: personal debt in English culture, 1740- 1914, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

83. An act for the more easy and speedy recovery of small debts within the parishes of Saint John the Baptist, Saint Peter the Apostle, and Birchington, and the Vill of Wood, in the Isle of Thanet, and County of Kent, 47 Geo III c7 1807.

84. Cinque Ports Act 1855, 17 & 18 Vict c48 1855.

85. John Lewis, The history and antiquities ecclesiastical and civil of the Ile of Tenet, in Kent, 1st edition, London, 1723.

86. The Margate Guide, 1770.

87. Kent Herald, January 22, 1829.

88. Kentish Gazette, August 7 1782.